History

of White Crane Kung fu |

| (Before

proceeding further, it is important to explain that there are

actually two martial art systems emanating from China that bear

the name of White Crane: one originates in Tibet and the other

in the southern coastal province of Fukien. Both arts are famous

and have glorious histories of their own. This fact is mentioned

in order to avoid confusing the public. Although rare in the western

world, Fukien White Crane is a famous fighting style in Southeast

Asia. In fact, it is widely considered to be one of the ancestors

of several traditional Okinawan Karate systems). We have presented

below a very detailed account of this artís history as it this

information is not readily available. To learn more about the

Fukien White Crane, itís history and theories, consult Shifu Lorne

Bernardís latest work ďShaolin

White Crane Kung Fu: A rare art revealed

|

|

The

history of the Fukienese White Crane Kung Fu has been passed down from

master to student (father to son) for five generations. Although various

accounts do exist, they all tell a similar tale. The history of White

Crane Kung Fu as passed down within the Lee family is presented below.

|

|

Fang

Chi-Niang was born in Lei Chow Fu in the middle of the 18th

century. Her father's name was Fang Hui Sz and her mother's name was

Lee Pik Liung. Fang Hui Sz studied Kung Fu in the Shaolin temple at

Nine Lotus Mountain, Ching Chiang district, Fukien (modern day Fujian)

province. His wife and daughter lived at Lei Chow Fu. Since they were

victimized by local landlords, it was decided to move away from the

village.

|

Eventually, they settled down in Ching Chu temple, on Ching

Chea Mountain (Lei Chow Fu). One day, as Fang Chi-Niang was drying grain

in front of the temple, she saw a huge crane come down from the roof

and begin to eat. She decided to use a bamboo stick to chase away the

intruder. Fang Chi-Niang was both curious and fearful of the crane.

At first, she tried to strike its head but the bird was evasive. Then

she attempted to hit the crane's wings but it stepped to the side and

used its claw to block the attack. When Fang Chi-Niang tried to poke

the bird's body with her staff, it moved back and used its beak to peck

the bamboo. Fang Chi-Niang was surprised. She continued to use the techniques

her father had taught her but her efforts were completely unsuccessful.

Astonished by the crane's skill, Fang Chi-Niang sought to practice with

it on a daily basis. Fortunately, the crane obliged. This permitted

Fang Chi-Niang to analyze and absorb the bird's self-defense strategies.

Eventually, she mastered the movements and spirit of the crane.

|

|

During

this period, Emperor Chien Lung ordered the destruction of the Southern

Shaolin temple after having been informed of revolutionary activities

on its grounds. Fang Hui-Sz was one of the few fortunate ones to escape

the attack. He sought out his wife and daughter and they initially settled

at Pik Chui Liang. Subsequently, Fang Hui-Sz moved to Sah Liang temple

near Foochow, where he spent his spare time refining his daughter's

Shaolin Kung Fu. Fang Chi-Niang eventually mastered everything her father

could teach her and chose to combine the crane's spirit and movements

with her Shaolin Kung Fu. She taught Kung Fu at Sah Liang temple to

Weng Wing-Seng, Lee Fah-Sieng, Chang The-Cheng, and Ling Te-Sun. Weng

was from Lei Chow Fu, Lee was from Chow Ann district, Chang was from

Wing Chun district, and Ling was from Foochow. Weng and Lee taught many

students at Kao Pei Cliff and set up a school there. Chang (nicknamed

Nine Dots monk) settled at the White Crane temple and taught martial

arts. Ling's descendants moved to Taiwan. Lee passed his skills to his

son Lee Mah-Saw. Lee Mah-Saw continued to set up schools and taught

in Chow Ann district. Fang Chi-Niang's teachings gave birth to different

interpretations and four principal styles were developed: Flying Crane

(Fei He), Eating Crane (Shi He) Screaming Crane (Ming He) and Sleeping

Crane (Jan He or Su He). Later on, variations and combinations with

other systems occurred which led to the creation of even more types

of Fukienese White Crane.

|

|

At

this point, it may be useful to debate whether the Fukienese White Crane

arts are truly Shaolin systems or whether they represent a separate

school. Since they were created outside the temple, many older generation

White Crane masters do not consider their art to be a Shaolin art. This

belief is compounded by the fact that White Crane focuses heavily upon

soft power in the advanced stages. On the other hand, the founder did

study from her father who was an accomplished Southern Shaolin practitioner.

Consequently, it is difficult to resolve the debate as it is largely

a question of perspective. Perhaps it is best to acknowledge the root

of the art while simultaneously recognizing the founder's unique contributions.

|

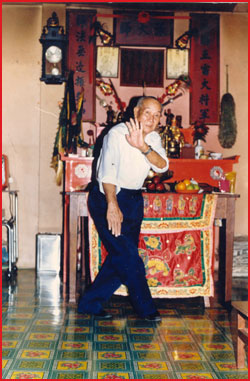

Grand-Master

Lee Kiang-Ke: Bringing White Crane into the 20th Century |

Historically,

with the end of feudal social systems and the widespread use of firearms,

advanced methods of combat are no longer an every day necessity. This

fact of life, combined with the traditionally secretive nature of kung

fu instruction, is contributing to the loss of an irreplaceable part

of China's cultural heritage. Many of the hundreds of different styles

of kung fu are in danger of being lost or diluted to the point of extinction.

For

practitioners of Fukien-style White Crane Kung Fu, the life of Grandmaster

Lee Kiang-Ke (1903-1992) represents both a link to the past and window

toward the future. To properly understand the reverence a martial artist

has for his or her Grandmaster, it is necessary to view the martial

art in its proper historical and cultural context. One important difference

between the martial arts and other forms of physical activity is that

martial arts can be practiced and enjoyed for a lifetime, and progress

can be made at virtually any age. As such, many older masters are considered

living treasures, due to the decades of accumulated knowledge, experience,

and teaching expertise that they possess. Today, fewer and fewer people

are willing to devote their lives to the study and teaching of martial

arts as was done in the past. Because of this unfortunate reality, priceless

martial knowledge often disappears forever upon the death of an elderly

Grandmaster. This is especially true in the many styles of Chinese martial

arts, where kung fu Shifus were secretive about their personal fighting

art, and unwilling to disseminate it indiscriminately.

Fukien

White Crane Kung Fu is continuing to thrive, thanks to the enlightened

thinking of one of its foremost proponents. Third-generation Grand-Master

Lee Kiang-Ke was the single most influential person responsible for

the preservation and dissemination of the flying crane system of Fukien

White Crane. His choice to open to the public what had previously been

a closed-door system ensured the survival of a most complete and devastating

Chinese martial art system.

|

|

Grandmaster

Lee Kiang-Ke (Lee Kiang-Kay) started to learn Kung Fu from his father

at the age of seven. After 10 years of arduous training, his father

sent him away to live at a temple (Bai He An) where he furthered his

martial knowledge under the instruction of a temple monk known as "Nine-dots

Monk." This temple specialized in the instruction of Fang Chi-Niang's

White Crane techniques. After four years of intensive study, the young

master returned home to assist his father in teaching White Crane and

in practicing herbal medicine. In time, he became the chief instructor

and medical practitioner in his community. Later on, the Kuomintang

(Chinese Nationalist government) invited him to join the 49th

Army Division as a medic. He ended up also teaching the soldiers the

long handled broadsword (Da dao).

|

|

When

his time of service was completed, he returned home and continued teaching

martial arts and practicing medicine. Thereafter, Lee Kiang-Ke moved

to Singapore where he stayed for six years. In an effort to escape the

Japanese invasion forces, he then moved to Kuching, East Malaysia. Unfortunately,

the Japanese invaded Malaysia soon after. Following the war, fellow

martial artists invited him to open a club. He did so and named it the

"Martial Heroes Association" (Woo Ing Tong)3. It prospered

for many years. During this period, Malaysian society was quite rough-and-tumble.

Polite tests of skill were fairly common. Less friendly challenges and

outright life and death self-defense situations also occurred. Master

Lee was famous amongst his peers for never losing a challenge.4

In 1963, he moved to the city of Sibu (also in the East Malaysian state

of Sarawak). Eventually, he directed several schools in local communities

including Kuching, Sibu, Sarikei, and Bintulu.

|

|

In

1967, the first South East Asian Kung Fu Tournament was held in Singapore.

Lee Kiang-Ke's Kung Fu brother, Lee Wen-Hung, came from China and competed.

Lee Wen-Hung had studied with Lee Kiang-Ke under Lee Mah-Saw. Despite

his somewhat advanced age, he won first place in combat. He then he

settled in Singapore. In 1973, a White Crane student representing Sarawak

(East Malaysia) went to compete in the third South East Asian Kung Fu

Tournament where he won second place in combat.

|

In

1967, the first South East Asian Kung Fu Tournament was held in Singapore.

Lee Kiang-Ke's Kung Fu brother, Lee Wen-Hung, came from China and competed.

Lee Wen-Hung had studied with Lee Kiang-Ke under Lee Mah-Saw. Despite

his somewhat advanced age, he won first place in combat. He then he

settled in Singapore. In 1973, a White Crane student representing Sarawak

(East Malaysia) went to compete in the third South East Asian Kung Fu

Tournament where he won second place in combat.

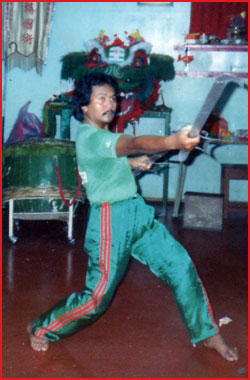

Grandmaster

Lee Kiang Ke retired in 1978 leaving his son, Shifu Lee Joo-Chian, the

leadership of the head school in Sibu, East Malaysia. Master Lee Joo-Chian's

own training reveals the hard work needed to acquire some real skill

(Kung Fu). Like his father, he started training at the age of seven.

Classes were generally two and a half hours long. As the climate is

hot and humid, warming up time was very brief. Students practiced forms

for a half hour without any break. Thereafter, they briefly rested and

recommenced their training of forms and basic moves for another half

hour. Two-person forms were then practiced for another half hour followed

by conditioning drills or weapons training. Finally, the last half hour

was reserved for free sparring practice. The young Lee Joo-Chian followed

this grueling schedule three times a day, six days per week! Morning

class was at 4.30 A.M. Then the children went off to school. Upon his

return, Lee Joo-Chian helped teach the afternoon class. Around eight

in the evening, Lee and his sisters trained once again. Master Lee likes

to remind people that there was little television in those days.5

|

|